Getting started with

Mentoring

What is mentoring?

Mentoring is the process by which an experienced and trusted colleague offers support, advice and guidance to another colleague. It involves transferring experience and expertise so that the less-experienced colleague can develop their skills and achieve their goals.

Functions of mentoring

There are two main functions of the mentoring relationship. The first is the ‘career function’, which helps mentees to learn their craft and prepare for progressing in their career. The mentor provides this function through the different ways that they offer advice and guidance. The mentor also acts as a role model and source of inspiration for the mentee. The second function is the ‘psychosocial function’, which focuses on the ways in which the mentoring relationship improves or strengthens the mentee’s confidence and personal growth. Mentors can also provide support to their mentees by offering acceptance, empathy and encouragement, and by demonstrating effective listening and questioning skills which support reflection.

Stages of mentoring

Mentoring is a developmental process which typically has three stages.

Stage 1: The mentee is more dependent

The mentor helps the mentee to achieve specific tasks related to their goals and they model skills, share strategies and provide feedback on observations. The mentor encourages the mentee and builds trust and confidence.

Stage 2: The mentee grows increasingly independent

The mentee becomes more self-directed in developing their skills, but also needs frequent feedback. The mentor questions the mentee and offers options, as well as directing the mentee to self-reflective practices which will help them evaluate their own progress.

Stage 3: The mentee and mentor depend on each other

The mentee becomes more reflective and relies less on the mentor. The mentee is able to find solutions, make decisions and solve problems. There is two-way discussion between the mentor and mentee and they plan together. The mentor provides a sounding board for discussion.

Mentors are guides. They lead us along the journey of our lives. We trust them because they have been there before. They embody our hopes, cast light on the way ahead, interpret arcane signs, warn us of lurking dangers and point out unexpected delights along the way.

In the rest of the unit, we will look at the basics of mentoring in more detail. We will discuss the benefits of mentoring, look at some research that supports mentoring and consider ways that it can work in practice.

Throughout the unit, we will encourage you to reflect on mentoring and think about how you can use it in your own school.

Listen to these educators discussing what mentoring means for them. How do their ideas about mentoring compare with yours?

What are the benefits of mentoring?

Benefits for the school or institution

Mentoring shows a school’s commitment to staff development.

Since mentoring promotes self-reflection and problem-solving in the mentee, it is an excellent form of professional development. The role of mentor is also a position of responsibility which develops leadership skills.

Mentoring helps a school to create a positive working environment.

Mentoring is goal-focused. The process of setting and achieving goals is empowering and builds confidence, which can transform the whole working environment.

Mentoring helps a school to keep staff and identify new talent.

Mentees have the opportunity to grow and develop in their practice. This makes it more likely that they will have job satisfaction, as well as being ready for career-development opportunities when they arise.

Mentoring helps a school to transform its teaching and learning.

Mentoring supports mentees in developing their classroom practice. This also means that students have the opportunity to learn more effectively and achieve better outcomes.

Benefits for the mentor

Mentoring develops the mentor’s communication and interpersonal skills.

A successful mentoring relationship depends on strong communication and interpersonal skills, which are transferable to every aspect of life. Mentors become skilled in rapport building and active listening, which allows them to ask valuable questions and offer feedback. These, in turn, build trust.

Mentoring develops the mentor’s leadership skills.

The key characteristics of good leadership are all fundamental to the mentoring process. These include: developing, enabling and influencing others, team work, communication skills and problem solving.

Mentoring allows the mentor to reflect on and develop their own practice.

Mentors draw on their own experience to give advice to mentees. This is a process which helps them to reflect on their own successes as they share them. Mentors may also develop new strategies as a result of helping a mentee to solve a problem that they are having.

Mentoring gives the mentors recognition as an expert

Mentors are valued by the mentee and by the school as a whole for the knowledge, skills and experience they possess.

Benefits for the mentee

Mentoring gives the mentee the opportunity to reflect and learn from the advice and experience of others.

Mentoring is a valuable way of sharing best practice.

Mentoring gives the mentee support to allow them to identify and achieve their goals.

The mentoring process is goal-oriented and solution-focused. Once goals are clearly defined, mentors can help mentees to break down their goals into manageable steps so that they can be achieved.

Mentoring gives the mentee encouragement to become more confident in their abilities and more involved in school life.

The mentoring relationship allows the mentee to reflect on what is going well and the ways in which they are moving towards their goals. Likewise, mentors are able to offer mentees exposure to aspects of school life that they would not otherwise gain experience of.

Mentoring gives the mentee tools and strategies to become a more independent, innovative and responsible learner.

Mentors direct mentees towards activities and practices which promote self-reflection. This means that over time, mentees become more empowered in making their own decisions and solving their own problems.

Listen to these educators giving their views on the benefits of mentoring. Which of the benefits are most relevant to you and your colleagues?

What is the research behind mentoring?

A number of adult learning theories contribute to a framework for mentoring in education.

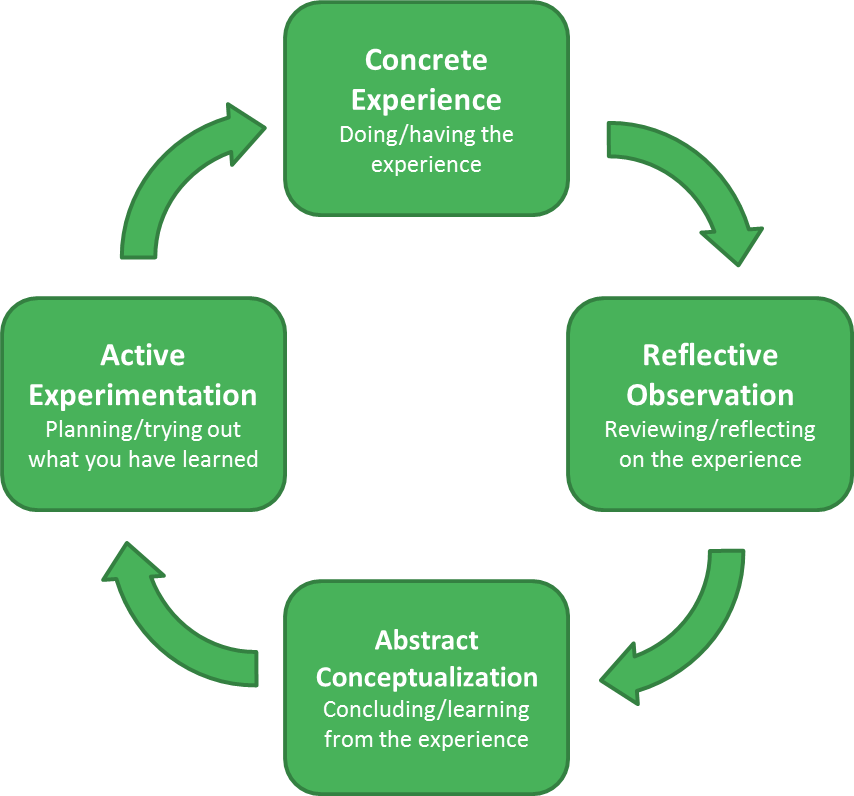

Kolb’s Theory of Experiential Learning is useful when mentees encounter a new experience. This could be, for example, teaching a new lesson they have planned. From this point, they reflect on and review the experience of the lesson. This review leads to learning and an action plan for future activities, which can then be tried out. The circle continues in this way, with learning from a previous activity informing the next activity.

Daloz’s Theory of Adult Learning demonstrates that the level of support and challenge provided by a mentor is critical. If the levels are too low, the mentee will not be challenged enough and they will receive so little support that the mentoring relationship may fail. If the level of challenge is too high, the mentee will not feel that they can achieve expectations and if the level of support is overbearing, it becomes impossible for the mentee to develop skills and knowledge of their own.

The Johari Window relates to how mentees become more aware of themselves and others. The mentor could use this tool to guide their mentee to consider different aspects of their personality and disposition, for example what they know about themselves and share with others (‘open’) and what they know about themselves but keep concealed (‘hidden’). The mentor can bring a different perspective, revealing traits the mentee may not be aware of (which are in their ‘blind spot’), and encouraging them to consider aspects of their personality that might be ‘unknown’, hidden in their subconscious or unconscious.

Brookfield’s Four Lenses model gives mentees the opportunity to explore different viewpoints and perspectives. Brookfield suggests that the goal of the critically reflective teacher is to gain awareness of their practice from as many different viewpoints as possible − their own, their students’, their peers’ and through engagement with theoretical literature.

Six common misconceptions about mentoring

‘Only mentees benefit from mentoring’

During the mentoring relationship, both the mentor and the mentee benefit and learn from each other. It is a great opportunity for both people to reflect and gain fresh perspectives. The mentor also gains personal and leadership skills which are valuable for their own career development, and they can gain a real sense of achievement in knowing they have made a difference to the mentee’s professional development. It is also likely that the mentor’s self-confidence will improve as they reflect on the experience they have to share.

‘Mentors have to be older than mentees’

Although a mentor may be older than the mentee, this does not have to be the case. Mentors should not be chosen for their age but for their expertise and experience and their ability to build relationships, listen, and share what they know effectively.

‘Having a mentor is a sign of weakness’

Colleagues at every stage of the learning process can benefit from mentoring and in many workplaces, mentoring will involve multiple relationships that span a mentee’s whole career. Having a mentor shows that you are willing to learn. It also shows that you are open to new perspectives and eager to progress and develop professionally.

‘Any experienced colleague can be a mentor’

Having the right experience and expertise to pass on to mentees is important, but it is not the only factor to consider when deciding who should be a mentor. Mentors also need to have excellent social skills so that they can build effective relationships with their mentees. The mentoring relationship can only be successful if understanding and trust are built between the mentor and mentee.

‘Effective mentors need to have all of the answers’

Mentors are role models, but the most effective mentors are those who understand and demonstrate that we are all still learning. A mentor does pass on experience and expertise which can benefit the mentee, but they also help by providing an opportunity for the mentee to talk through their problems and be listened to. Through their skills in listening and questioning, mentors can also help mentees to find their own answers.

‘Mentoring requires a greater time commitment than teachers can afford’

Mentoring is a great way to invest a small amount of time and achieve great results. As well as observing lessons, mentoring involves mentors meeting regularly with their mentees, but these meetings do not have to be long and can involve as little time as 30 minutes every week or fortnight. Mentors can make sure that the time they commit is manageable by setting clear boundaries around the times when they are available. Also, mentoring sessions are a great opportunity to gain new perspectives on work and to re-establish priorities, which can mean that both the mentor and the mentee work more effectively.

Mentoring in practice

The mentoring relationship is based around regular communication in the form of mentor meetings, as well as informal communication between meetings. ‘Mentoring moments’, which are moments where the mentor’s input and support make a significant difference to the mentee, can happen in formal, planned moments or more informally. However, in order to make these moments more likely to happen, it is important that mentor relationships and meetings are successful. Here, two main areas need to be considered: the mentoring process, and mentoring tools and strategies.

The mentoring process

Mentor meetings

Regular mentor meetings are the foundation of the mentoring relationship. Before the mentoring process begins, it is important that the details of the meetings are organised.

Where?

It is important to consider where the meetings will be, making sure that the location will always be available, and that it is private and contributes to a positive mutual relationship being built. For example, a neutral setting may be best, with the furniture laid out so that the mentor and mentee can sit together rather than on opposite sides of a desk.

How often and for how long?

Meetings could take place every one or two weeks, and last for 30 minutes or an hour. It is important to leave enough time between meetings for the mentee to be able to carry out their action plan. In some mentoring relationships, arrangements may not be as formal as having set times for meetings, but it is important that the level of structure is established at the beginning of the relationship so that both the mentor and the mentee are clear about the expectations.

The first meeting

The first meeting is an opportunity for the mentor and the mentee to get to know each other better and build a relationship. It is also an important time to establish ‘ground rules’ for future meetings. There are a number of things to consider here:

• What level of challenge is the mentee comfortable with?

• Would the mentee prefer more guidance or more of a coaching style?

• Are the mentor and the mentee expected to take notes?

• What is the system for reviewing the meetings?

• Is the mentor available between sessions?

• What are the expectations relating to the mentee completing follow-up tasks after a meeting?

The more the mentor and mentee understand about each other’s expectations at the beginning of the relationship, the more likely it is to be successful.

It is also important at this point to establish the boundaries of the relationship, such as how personal issues will be dealt with and discussed if they are affecting the mentee’s performance at work, as well as situations where others, such as the mentee’s line manager, may be involved in the process. Setting boundaries also relates to the confidential nature of the relationship and any arrangements necessary to establish this.

Building the relationship

Once the mentoring relationship is established, the typical agenda for a mentor meeting is based on the mentee’s goals. It could include the following:

1. Greeting

2. Confirming the agenda

3. Reviewing the previous meeting and action taken

4. Feedback and discussion

5. Setting a new action plan and targets

6. Reviewing the meeting

7. Agreeing the details of the next meeting

Contact between meetings

While it is important that contact is maintained between meetings, the nature of that contact should be decided beforehand. For some mentoring pairs, the mentor may feel comfortable inviting the mentee to contact them at any time. Others may establish a system of meeting more informally between meetings or being available via email if the mentee has any problems or concerns.

Reviewing progress

As well as reviewing what has been achieved after each meeting, it is also important to establish routines for providing scheduled feedback during the mentoring process. This might be after a specific number of sessions or when the mentee has reached a particular milestone. This will provide a record of the progress the mentee has made towards achieving their goals and draw out key learning from their experiences. It is also a valuable way of highlighting the effectiveness of the mentoring relationship and anything that can be improved as the relationship progresses.

The end of the programme

As the mentee reaches the end of the programme, they may already have become more independent. In this case, it might be appropriate to have meetings less often or reduce the time each meeting lasts. At the end of the programme it is helpful to have a final conversation. This may not be as formal as the other meetings, but it is important to make sure that the mentee’s success is celebrated and that the mentor passes on any final feedback. It is also a good opportunity to establish the future contact the mentor and mentee will have.

Mentoring tools and strategies

Here are five ways that mentors can build rapport with their mentees and ensure they get the most out of meetings:

1. Active Listening

In effective mentor meetings, listening goes beyond simple conversational listening to active listening. Here, the mentor switches off both internal and external distractions to allow them to focus more carefully on what the mentee is saying. This also means it is more likely that the mentor will be listening for much more time than they are talking. During active listening, the mentor pays close attention to what is being said, but also considers the mentee’s tone, body language and facial expressions, and is aware of what is not being said.

Active listening takes lots of practice, but it is very rewarding. Before a mentoring session, it is important that the mentor removes any potential barriers to listening, distractions and sources of stress, and makes sure that the meeting area is physically comfortable so that they can practise active listening.

2. Giving feedback

Feedback is most effective when it follows active listening. In fact, feedback is a useful way that mentors can demonstrate they have been listening and check they have understood what the mentee is saying by either summarising (which is where the mentor repeats a shortened version of what has been said using the mentee’s own words) or paraphrasing (which is where the mentor uses their own words to convey the sense of what the mentee has said).

It is important that feedback is balanced and constructive. Feedback is particularly effective when it is based on

evidence and linked to the mentee’s strengths. Beginning with evidence makes the feedback more believable and linking the evidence to strengths builds a mentee’s confidence. For example, ‘The way you explained the seating plan in your classroom shows that you really consider every student’s learning needs.’ From this point, the mentee is more empowered to move forward with how they might develop or improve.

3. Questioning

Effective questioning is a very important part of mentoring. There are two main types of questions − open and closed. Closed questions are generally not helpful in mentoring as they restrict a mentee’s responses, often to simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers, and do not require a mentee to think deeply about their response. Closed questions begin with phrases such as ‘Do you…?’, ‘Have you…?’, ‘Is there…?’ Mentors should avoid closed questions (along with leading questions) as they restrict a mentee’s ability to speak freely.

Open questions are powerful tools for mentors. They begin ‘What…?’, ‘Where…?’, ‘When…?’ and ‘How…?’ Open questions help a mentor to be non-judgemental and understand their mentee, to gather information, and to raise the mentee’s awareness of their situation so that they can find new ways forward.

There are different types of open questions, and the power of a good mentor lies in being able to ask the right question at the right time. Here are some examples of different kinds of open questions.

• Wisdom-accessing questions establish motivation. For example, ‘What are you hoping to gain from this?’

• Probing questions find out more or dig deeper. For example, ‘How do you know this is right for you?’, ‘How will you look back on this?’

• Hypothetical questions temporarily remove barriers to success to find new ways forward. For example, ‘If there were no limits to resources, what would you do?’

Reflective questions draw on knowledge a mentee already has. For example, ‘Knowing what you know now, how could you have done things differently?’

4. Problem solving techniques

As well as effective questioning strategies, there are a number of problem-solving techniques that can help a mentee to consider their situation from different perspectives, making a discussion more productive and focused.

One example of this is de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats. Each different-coloured hat represents a different viewpoint about the situation. By mentally ‘switching hats’, a mentee can gain new perspective.

Other popular problem-solving techniques include: SWOT analysis, fishbone analysis, force field analysis and simple brainstorming or lists of pros and cons.

5. The ‘GROW’ Model

The GROW model is a useful coaching model which can be used to structure mentoring meetings, in order to make them effective and purposeful.

The model is based on a four-stage cycle.

(i) Goal: What do you want?

The topic for discussion is established and the mentee explores their ideal outcome and what they want to achieve by the end of the session in relation to this outcome.

(ii) Reality: What is happening?

The mentee explores where they currently are in relation to their goal, including the positive things that can help them to move towards it and any potential barriers.

(iii) Options: What could you do?

The mentee considers all the different options available to them. The aim is to create a variety of possible alternatives which have not previously been considered.

(iv) Will: What will you do?

The mentee establishes the specific actions they will take to put their options into practice and take the next step towards their goal.

Checklist for the programme

When considering a mentoring programme it is important that you consider how you will make sure a culture of mentoring is at the heart of your institution. To do this it is vital that senior leaders support and even contribute to the programme, otherwise it will be harder to make it stick and to feel the long-term benefits of mentoring. The following checklist will encourage you to think about the questions you should ask as you set up your programme.

1. How will I make sure that the mentoring scheme is supported by school leadership and the organisation as a whole?

It is important to begin by establishing mentoring within the leadership team of the school or institution. This involves making sure the whole leadership team has a shared understanding about what mentoring is and a commitment to developing mentoring. The leadership team can then make sure that the mentoring programme is in line with the school’s strategic vision.

2. How will I promote the mentoring scheme and attract teachers who have the potential to be mentors?

How will you raise staff awareness about mentoring? Who is in the best position to be able to give this information? What criteria will you use to identify potential mentors? Are there any members of staff who have previous experience of mentoring? Will there be a formal application process?

Qualities of a good mentor that you may want to consider include the following:

• Someone who is credible in their role and able to act as a role model.

• Someone who is genuinely interested in developing themselves and others.

• Someone who is open and willing to share their experiences, both good and bad.

• Someone who has effective listening and questioning skills.

• Someone who is able to offer encouragement as well as provide useful feedback in a non-judgemental way.

• Someone who will respect the boundaries of confidentiality in the mentoring relationship.

3. What protocols and procedures will need to be put in place to support the mentoring programme?

• Who will be responsible for managing and co-ordinating the mentoring scheme, and developing the protocols and procedures in your school or institution?

• Will there be a formal mentoring agreement? Will this include a statement about confidentiality? What other paperwork will be necessary to keep a record of discussions?

• What are the timetabling requirements of the mentoring programme? Are there suitable places to meet? When will meetings take place? Will time be provided for meetings during the working day or will they be expected to take place outside working hours? How often will mentor meetings take place and how long will they be? What arrangements need to be made to allow lesson observations to take place?

• What training and ongoing support will mentors need and how will this be provided?

4. How will mentoring partnerships be established?

When matching mentors and mentees, it is important that it is relatively easy for the mentee to be able to make contact with the mentor. It is also important that the mentor does not have any line-management responsibilities for the mentee, as this would make it more difficult to build an atmosphere of openness and trust.

• Who will be responsible for creating mentoring partnerships?

• How will this person check that mentors and mentees are compatible in terms of styles and personalities?

5. How will the effects of the mentoring scheme be monitored and evaluated?

It is important to consider how far the mentoring programme is fulfilling its intended outcomes, while making sure that the evaluation process does not become an opportunity to assess and report on a mentor’s performance or reveal the content of discussions in the mentoring meetings.

There are different aspects of a mentoring programme which can be monitored and evaluated.

Programme processes

This might include evidence of a pattern of regular contact over the agreed term, commitment of mentors and mentees to the programme and levels of satisfaction with the programme.

Participant experiences

This might include evidence of the perceived value of the programme by both the mentor and the mentee, levels of trust felt by the mentor and the mentee, job satisfaction and career progression over time.

Organisational outcomes

This might include evidence of work performance of the mentor and the mentee (this could be both in terms of classroom practice and student outcomes), recognition of the programme within the organisation and how mentoring helps you to keep staff.

What outcomes will you measure the mentoring programme against? How will you measure the effects of your mentoring programme? Will the information you collect relate to the quality or the amount of mentoring provided, or a mixture of both? At what point (or points) in the programme will you ask for feedback? Will the feedback be provided at the end of the programme, during the programme or a mixture of both?

Checklist for mentors

If you are new to being a mentor and want to decide if it is right for you, it will help to ask yourself the following questions.

1. Do I have the time and space to meet regularly with my mentee?

Working lives can be very busy, so it is important to be sure that you will be able to provide time and space away from distractions so that your mentee feels appropriately supported and listened to.

2. Do I have a high level of knowledge and experience in my role?

As well as being able to be a role model and demonstrate good practice to mentees, it is also important that you have an understanding of things the mentee would like to achieve so that you can pass on appropriate advice. If the mentee is being mentored because they want to achieve a professional qualification, it is also important that you have an understanding of the qualification and the programme of study.

3. Do I have a genuine interest in developing others?

The ability to develop others so that they can reach their potential is an important skill in leadership as well as in mentoring. Mentors must recognise that we are all still learning and be able to look at a mentee’s potential problems as opportunities to grow and learn.

4. Do I have evidence of having strong social and listening skills?

Strong social skills are essential in order to be an effective mentor. However, you do not necessarily need formal training in these skills, as the process of being a mentor helps to develop them.

5. Am I trustworthy and can I respect confidentiality boundaries?

Effective mentoring relationships are built on trust. This is important so that the mentee feels that they can be open and share concerns or difficulties with you that they may feel less comfortable sharing with other people or their managers. It is also important that you are able to keep the content of the discussions you have with your mentee confidential.

Next steps

Here are some practical things you can do to begin the process of setting up a mentoring programme in your school.

1. Establish the aims and outcomes of mentoring in your school or institution

Aims are the overall intentions for the mentoring programme and outcomes are what will happen as a result of it. Write down the aims that you have for your mentoring programme in terms of what you want it to achieve.

The Standard for Teachers’ Professional Development also provides a useful framework to measure the outcomes of a mentoring programme. The standard states that professional development should:

• improve and evaluate student outcomes;

• be supported by strong evidence and expertise;

• include working with others and expert challenge;

• be maintained over time; and

• be prioritised by school leadership.

For each for these five points, outline how your school’s mentoring programme will fulfil the standard.

2. Establish your school’s or institution’s ability for mentoring

It is important to decide how mentoring will meet staff needs and so who mentoring will be offered to in the first year. For example, it could be for new teachers, staff completing professional development programmes, or all staff. It is also important to decide whether staff will be recommended for mentoring or whether they can volunteer to be mentored.

3. Write an action plan for introducing mentoring in the school or institution

In order for the mentoring programme to become part of the school’s or institution’s strategic vision, it is important to create an action plan. For each part of the programme this should include aims and objectives, actions, dates, support and resources needed, success criteria and the person responsible.

Here is an example of one part of an action plan for a mentoring programme.

Here are some practical things you can do if you are going to begin mentoring

1. Talk to the mentor co-ordinator

Find out from the mentor co-ordinator what their expectations are for the mentoring relationship. You could also ask for some initial background information about your mentee, why they have been selected for mentoring and what the intended outcomes of mentoring are for the mentee.

2. Exchange details with your mentee and find out what they want to achieve from mentoring

Depending on whether you already know your mentee, and how well, it will be useful to find out some information from them. This should include personal information such as contact details, as well as professional information such as their career background and what role they currently have. At this point, it is also useful to find out what the mentee wants to gain from the mentoring experience and the key areas which you can provide support in. Make sure you share information about yourself with your mentee, as getting to know each other will help to build the relationship.

3. Arrange the practical details and structure of the sessions

Decide when and where you will meet, and also how often meetings will be held and how long they will last. Also, establish the principles of how you will work together and your expectations of each other. This may include things such as whether the mentor and the mentee are expected to take notes, follow-up tasks and feedback, as well as more formal contracts such as confidentiality agreements.

Want to know more?

Here is a printable list of interesting books, articles and websites on the topics that we have looked at.