Getting started with Effective Questioning

Cambridge International Education

Teaching and Learning Team

What is effective questioning?

Questioning is an important principle of teaching and a powerful tool for teachers and learners across different subjects and phases. We know that effective questioning helps learners to consolidate, deepen and extend their thinking and learning. It encourages them to think hard, not just about answers but about the learning process itself.

It is easy to see why questioning is an essential part of the learning journey. As a core part of assessment for learning, it helps you to know where learners are on their journey, where they need to be and what they need to do to get there. Also, it allows you to give and, importantly, receive feedback at any given point in the lesson. Effective questioning is responsive, dynamic, and has a significant influence on learning, enabling you to make changes at the right time to get the best out of learners.

You can watch this video to hear ideas about what effective questioning is and how it can benefit learners

Being clear about the purpose of questions can help you frame questions more carefully. However, it is important to remember that there are lots of different and valid reasons why teachers use questioning. It helps to:

- focus on a topic and draw out learners’ knowledge;

- ignite curiosity and engage learners more;

- guide thinking and learning;

- deepen thinking and extend learning;

- stretch and challenge all learners;

- systematically assess learning and check understanding;

- inform teaching, helping teachers to adapt content to meet learners’ needs;

- identify and respond to gaps and misconceptions in knowledge and understanding;

- scaffold understanding to support learners towards their goals;

- make links and connections across topics and subjects so that learning can be transferred; and

- encourage learners to reflect and to identify the next steps to move learning forward.

Effective questioning is a fundamental part of successful learning and progress and plays a crucial role in every classroom. If you walk into most lessons, at some point you will see teachers and learners in question-and-answer routines, or learners answering written questions. So investing time in improving the quality of questioning matters.

Our aim in this guide is to build a shared understanding that the main purpose of effective questioning is to help learners to think and teachers and learners to assess progress, adapt teaching and move learning on. We also aim to provide you with a range of innovative and practical strategies which you can use when teaching.

What is effective questioning?

Questioning is an important principle of teaching and a powerful tool for teachers and learners across different subjects and phases. We know that effective questioning helps learners to consolidate, deepen and extend their thinking and learning. It encourages them to think hard, not just about answers but about the learning process itself.

It is easy to see why questioning is an essential part of the learning journey. As a core part of assessment for learning, it helps you to know where learners are on their journey, where they need to be and what they need to do to get there. Also, it allows you to give and, importantly, receive feedback at any given point in the lesson. Effective questioning is responsive, dynamic, and has a significant influence on learning, enabling you to make changes at the right time to get the best out of learners.

You can watch this video to hear ideas about what effective questioning is and how it can benefit learners

Being clear about the purpose of questions can help you frame questions more carefully. However, it is important to remember that there are lots of different and valid reasons why teachers use questioning. It helps to:

- focus on a topic and draw out learners’ knowledge;

- ignite curiosity and engage learners more;

- guide thinking and learning;

- deepen thinking and extend learning;

- stretch and challenge all learners;

- systematically assess learning and check understanding;

- inform teaching, helping teachers to adapt content to meet learners’ needs;

- identify and respond to gaps and misconceptions in knowledge and understanding;

- scaffold understanding to support learners towards their goals;

- make links and connections across topics and subjects so that learning can be transferred; and

- encourage learners to reflect and to identify the next steps to move learning forward.

Effective questioning is a fundamental part of successful learning and progress and plays a crucial role in every classroom. If you walk into most lessons, at some point you will see teachers and learners in question-and-answer routines, or learners answering written questions. So investing time in improving the quality of questioning matters.

Our aim in this guide is to build a shared understanding that the main purpose of effective questioning is to help learners to think and teachers and learners to assess progress, adapt teaching and move learning on. We also aim to provide you with a range of innovative and practical strategies which you can use when teaching.

What are the benefits of effective questioning?

Effective questioning develops critical thinking skills

All teachers need to teach learners to think critically, both at school and beyond. Effective questioning develops critical thinking skills, allowing learners to make connections, make sense of the world they live in and deal effectively with new situations. This is particularly relevant when learners are taking exams because it gives them the confidence and skills to tackle questions that are both familiar and unfamiliar.

Effective questioning enables teachers to assess learning

All teachers are assessors of learning, and questioning is a basic tool in allowing teachers to do this. Asking the right questions can help you assess understanding. This allows you to use questions to scaffold learning carefully, adapting your teaching to help individuals and groups make progress.

Effective questioning develops metacognition

When teachers and learners ask questions aloud, it makes thinking ‘visible’ and helps the learner to take control of their thinking. Instead of focusing on outcomes, they focus on the process of learning. Self-questioning in particular is an important part of the planning, monitoring and evaluation phases of metacognition.

For example:

Planning - what do I already know that will help me with this task?

Monitoring − is the strategy I am using working?

Evaluation − what would I do differently next time?

Effective questioning promotes active learning

Effective questioning is at the heart of active learning because it makes learners think hard and places them at the centre, whether they are asking questions or responding to them.

Effective questioning stretches and challenges

It is important to remember that the teacher should not be the only person asking questions. When you give learners the opportunity to ask questions and build this into their day-to-day practice, this can take learning in different directions, by stretching, challenging and adding depth.

What does the research say about effective questioning?

Questioning forms an important part of classroom discussion. Educational research tells us that classroom discussion can have a significant impact on learning, progress and achievement. Hattie (2009) uses effect sizes to measure the effectiveness of different teaching strategies and interventions on student achievement. Effect sizes are numbers that show the size of any difference between two data sets, taking into account the spread of the data. This can help teachers to invest their time in the things that make the most difference. Hattie’s research calculates the effect size of questioning at 0.82, which is above average, demonstrating that effective questioning has a positive impact on learning.

This becomes more powerful when we take it a step further and look at questioning as a major part of the feedback cycle. Hattie (2009) gives feedback an effect size of 0.73 and identifies that, when it is done well, it can be one of the most effective factors in improving student achievement. Feedback has a number of purposes in this context. Fundamentally, questioning provides teachers with feedback on how effective their practice is.

‘It was only when I discovered that feedback was most powerful when it is from the student to the teacher that I started to understand it better.’

Educational research also shows that effective questioning can significantly develop oracy, helping them to express themselves more confidently. Alexander (2015) and Mercer and Hodgkinson (2008) investigate the role of talk in the classroom and point to how effective questioning by the teacher can lead to this. Through their work, they explore the power of dialogic teaching and dialogic talk − in other words, the power of collaboration and dialogue to aid thinking, learning and assessment.

What does the research say about effective questioning?

Questioning forms an important part of classroom discussion. Educational research tells us that classroom discussion can have a significant impact on learning, progress and achievement. Hattie (2009) uses effect sizes to measure the effectiveness of different teaching strategies and interventions on student achievement. Effect sizes are numbers that show the size of any difference between two data sets, taking into account the spread of the data. This can help teachers to invest their time in the things that make the most difference. Hattie’s research calculates the effect size of questioning at 0.82, which is above average, demonstrating that effective questioning has a positive impact on learning.

This becomes more powerful when we take it a step further and look at questioning as a major part of the feedback cycle. Hattie (2009) gives feedback an effect size of 0.73 and identifies that, when it is done well, it can be one of the most effective factors in improving student achievement. Feedback has a number of purposes in this context. Fundamentally, questioning provides teachers with feedback on how effective their practice is.

‘It was only when I discovered that feedback was most powerful when it is from the student to the teacher that I started to understand it better.’

Educational research also shows that effective questioning can significantly develop oracy, helping them to express themselves more confidently. Alexander (2015) and Mercer and Hodgkinson (2008) investigate the role of talk in the classroom and point to how effective questioning by the teacher can lead to this. Through their work, they explore the power of dialogic teaching and dialogic talk − in other words, the power of collaboration and dialogue to aid thinking, learning and assessment.

Six common misconceptions about effective questioning

Some teachers are naturally good at questioning, it is something they can ‘just do’.

To develop their questioning, teachers need to deliberately use different strategies, techniques and approaches. When trying out these different approaches, highly effective teachers then evaluate their practice to explore what has the greatest impact on learning.

Closed questions have less value than open questions.

Closed questions are just as important as open questions in learning, particularly when they are used to check and reinforce knowledge. Closed questions can also build learners’ confidence with subject content.

When learners ask lots of questions, it means the teaching isn’t very effective.

Great teaching and learning involves children and young people being curious and asking their teacher and their peers lots of questions. When learners ask questions, it helps you to identify which misconceptions and gaps in learning you need to address.

Fast-paced questioning is especially effective.

Fast-paced questioning may hold the attention of a class, but because learners do not have time to process the question or come up with a considered response, it is not the most effective way of stretching learners. Responses to fast-paced questions tend to be superficial. You are more likely to get thoughtful responses if you give learners thinking or wait time.

Teachers should know all the answers.

Teachers don’t have all the answers. One of the joys of teaching is that, as the teacher, you sometimes get to learn with your class. The most effective teachers see themselves as learners.

Getting the answer right is essential.

This is not always true. Often, the process of learning is either more important, or just as important, as getting the right answer.

Effective questioning in practice

It is helpful to use a range of different questioning strategies. In this section we are going to explore six effective questioning strategies that you can use in the classroom.

- Creating the right classroom climate

- Choosing the right questions

- Types of questions

- Stategies for assessing learning and checking understanding

- Stategies for promoting, deepening and extending thinking

- Getting learners to ask better questions

1. Creating the right classroom climate

Creating the right climate in the classroom is important for learners to grow and thrive. We know that people learn well when they feel safe and valued. When the classroom climate is good, learners feel able to take risks and don’t worry about making mistakes. In many ways, mistakes are seen as an important part of learning. As teachers, it is important that we set high expectations in terms of the behaviours we expect from learners, and lead by example to show the benefit of making mistakes and taking considered risks.

Some examples of good practice are shared in this video

Effective questioning in practice

It is helpful to use a range of different questioning strategies. In this section we are going to explore six effective questioning strategies that you can use in the classroom.

- Creating the right classroom climate

- Choosing the right questions

- Types of questions

- Stategies for assessing learning and checking understanding

- Stategies for promoting, deepening and extending thinking

- Getting learners to ask better questions

1. Creating the right classroom climate

Creating the right climate in the classroom is important for learners to grow and thrive. We know that people learn well when they feel safe and valued. When the classroom climate is good, learners feel able to take risks and don’t worry about making mistakes. In many ways, mistakes are seen as an important part of learning. As teachers, it is important that we set high expectations in terms of the behaviours we expect from learners, and lead by example to show the benefit of making mistakes and taking considered risks.

Some examples of good practice are shared in this video

2. Choosing the right questions

‘Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students: questions help students practise new information and connect new material to their prior learning.’

On average, teachers ask approximately 400 questions per day. Rosenshine (2012), in his ‘Principles of Instruction’, supports the view that the most effective teachers ask more questions than the least effective teachers. However, he makes the point that asking probing and thoughtful questions is challenging and suggests that teachers should aim to ask more high-quality questions. Planning and choosing the right question is an essential part of this.

Effective teachers plan sequences of questions carefully to encourage thinking, assess progress and move learning on. To plan questions effectively, teachers need good subject knowledge, and they need to know what the end point is, otherwise the lesson can lose focus.

Here is an example of how a science teacher used a sequence of questions to help learners evaluate the method they had used in a science experiment.

- Which methods did you consider? Did anyone consider any other methods?

- Which method did you choose? Why did you choose that method?

- How effective was your method? What were the benefits and drawbacks?

- What do you know now that you didn’t know before? What was new?

- Could you use what you learned in a different situation? In a different subject?

- Is there anything you still need to find out or consider?

- If you could do the experiment again, what would you do differently? What else?

- What do you notice about the sequence of questions?

- What feedback would you give the teacher about their questioning?

- What does this mean for your own questioning?

Listening is also important when choosing the right question. Effective teachers listen carefully to learners and ask questions to clarify, probe, extend and refine their responses. Active listening means that the teacher can choose and shape the question to support or stretch learners. Ultimately, listening and responding focuses on learning as a process rather than an event.

3. Types of questions

Questions are often divided into two broad categories: closed questions and open questions.

Closed questions often involve the recall of facts and knowledge previously taught and usually require a short answer, for example, yes or no or true or false.

- Is Romeo a Montague or a Capulet?

- Is _______ an acid or alkali?

- Is 5 a prime number?

- Is the word ______ masculine or feminine?

- What is the capital city of Australia?

Open questions usually require more thinking and can have more than one possible answer. They can focus on a topic, subject or the learning process. They often explore things in greater breadth or depth.

- What do we know about the Romans?

- What makes a good leader?

- How could we make the world a fairer place?

- Should children get paid to go to school?

- Is this the best way to solve this problem?

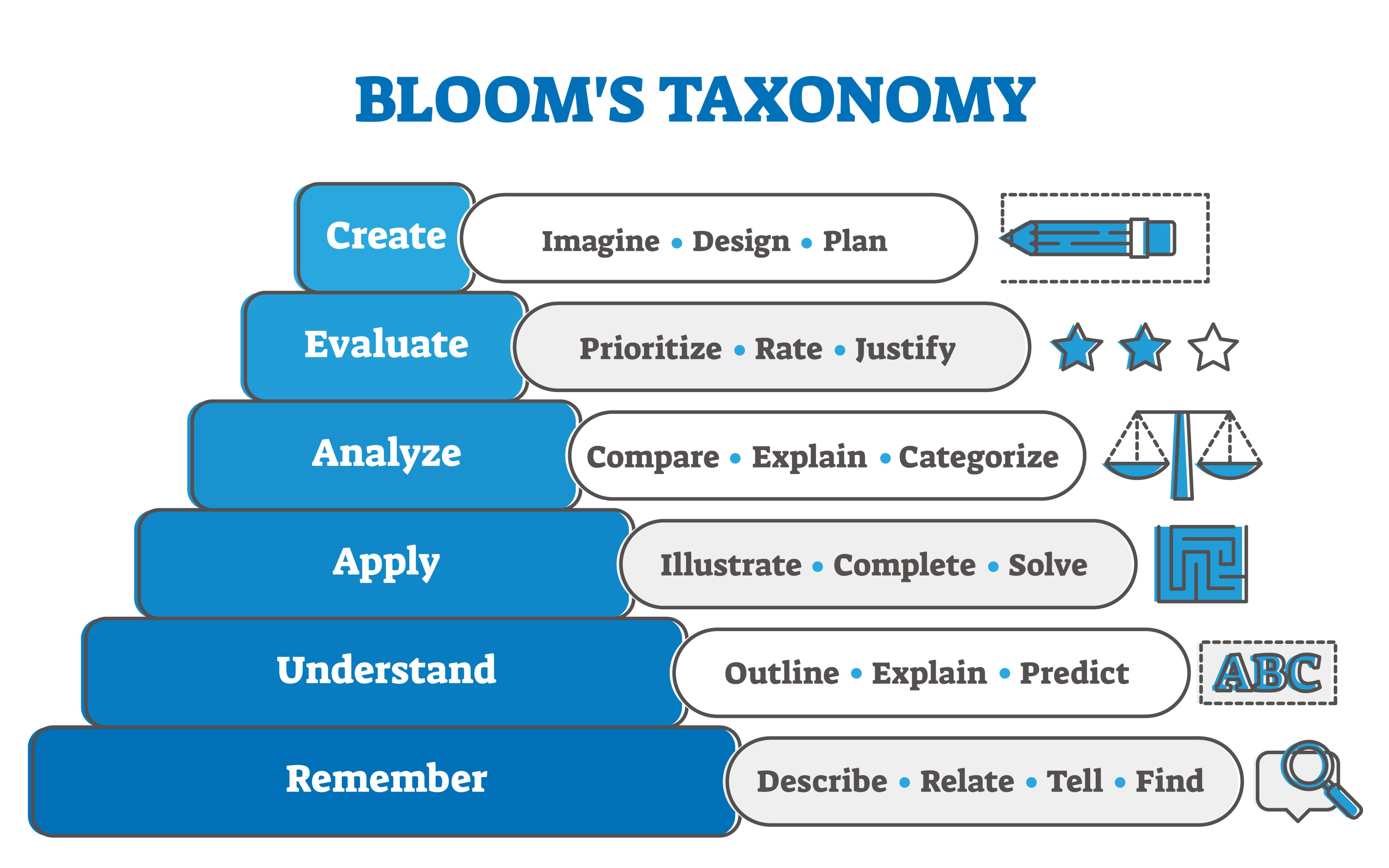

Both closed questions and open questions have huge value. Closed questions can help learners to retrieve and build knowledge, while open questions help them to consolidate, extend and apply knowledge in a range of different contexts. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) emphasise this in their revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, where the steps of thinking are structured to reflect the complexity of cognitive processing. For example, analysing is more complex than remembering, but it is not necessarily more important in the learning process.

Ritchhart (2009) in his Cultures of Thinking Project took this further and identified a different ‘Typology of Classroom Questions’ in order to make thinking and learning more visible in the classroom. He gives examples of what each type of question could look like to support teachers. Through his work with Project Zero at Harvard University, he classified the following types of questions.

- Review: recalling and reviewing knowledge and information

- Procedural: directing the work of the class

- Generative: exploring the topic

- Constructive: building new understanding

- Facilitative: promotes the learner’s own thinking and understanding

Thinking about the types of questions we ask is important to make sure that we are stretching and challenging all learners and helping them to learn effectively.

Building a questioning toolkit is a great place to start in terms of developing as a teacher. Deliberate practice is an important part of this. The next section offers a range of innovative and practical strategies that you can try out.

3. Types of questions

Questions are often divided into two broad categories: closed questions and open questions.

Closed questions often involve the recall of facts and knowledge previously taught and usually require a short answer, for example, yes or no or true or false.

- Is Romeo a Montague or a Capulet?

- Is _______ an acid or alkali?

- Is 5 a prime number?

- Is the word ______ masculine or feminine?

- What is the capital city of Australia?

Open questions usually require more thinking and can have more than one possible answer. They can focus on a topic, subject or the learning process. They often explore things in greater breadth or depth.

- What do we know about the Romans?

- What makes a good leader?

- How could we make the world a fairer place?

- Should children get paid to go to school?

- Is this the best way to solve this problem?

Both closed questions and open questions have huge value. Closed questions can help learners to retrieve and build knowledge, while open questions help them to consolidate, extend and apply knowledge in a range of different contexts. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) emphasise this in their revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, where the steps of thinking are structured to reflect the complexity of cognitive processing. For example, analysing is more complex than remembering, but it is not necessarily more important in the learning process.

Ritchhart (2009) in his Cultures of Thinking Project took this further and identified a different ‘Typology of Classroom Questions’ in order to make thinking and learning more visible in the classroom. He gives examples of what each type of question could look like to support teachers. Through his work with Project Zero at Harvard University, he classified the following types of questions.

- Review: recalling and reviewing knowledge and information

- Procedural: directing the work of the class

- Generative: exploring the topic

- Constructive: building new understanding

- Facilitative: promotes the learner’s own thinking and understanding

Thinking about the types of questions we ask is important to make sure that we are stretching and challenging all learners and helping them to learn effectively.

Building a questioning toolkit is a great place to start in terms of developing as a teacher. Deliberate practice is an important part of this. The next section offers a range of innovative and practical strategies that you can try out.

4. Strategies for assessing learning and checking understanding

No hands up or direct questioning. To direct specific questions to learners, a ‘no hands up’ approach can be helpful as it means you can differentiate questions. It can also involve more learners, as there is a possibility anyone could be asked a question. To add another challenge, aim to ask a learner two questions in succession. The second question should probe and encourage extended responses.

Zero-stakes testing. A zero-stakes testing approach is when learners test or assess themselves. Their answers or results have no effect on grades or results and the teacher doesn’t know or collect the answers. Only the learner knows whether they can or cannot do something. This is valuable because it motivates the learner to work out the answer or work out how to do something independently. As a result, their resilience and ability to be self-directed improves.

Hinge questions. A hinge question is based on an important concept in a lesson that is critical for all learners to understand before you move on.

- The question may fall about midway through the lesson.

- It is usually a multiple-choice question with three or four possible answers.

- Each incorrect answer reveals a possible misconception to probe.

- Every learner must respond to the question within two minutes.

- You must be able to collect and interpret the responses from all learners in 30 seconds.

- Mini whiteboards can be helpful in involving the whole class.

Here is an example for maths:

Choose the best description of a rhombus.

(a) A 2D shape with two pairs of parallel sides.

(b) A quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides, each side being of equal length.

(c) A quadrilateral where all four sides have equal length. Opposite sides are parallel and opposite angles are equal.

(d) A quadrilateral where all four sides have equal length. Opposite sides are parallel and all angles are right angles.

Relay technique

After you have explained a topic or asked or a series of questions on a topic, ask a learner to relay back or explain what they have understood. This gives the learner the opportunity to demonstrate what they have understood and allows you to fill gaps and identify misconceptions.

Say it again, say it better

You ask a learner to give an initial response to a question. The learner might make a false start, stumble or hesitate as they work out their response. You allow this but then ask the learner to ‘Say it again, say it better.’

Low-stakes quizzes and retrieval practice

Low-stakes quizzes, or tests, are short quizzes that have no effect or influence on grades or results. They are a good way to check surface learning and support learners to practice retrieving knowledge. They work well as starter activities and can often be marked by the learner or their peers. They support learners’ ability to remember and retrieve important information and are often used to identify misconceptions or learning that is not yet secure.

5. Strategies for promoting, deepening and extending thinking

‘I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only teach them to think.’

Wait time

It is estimated that learners on average only have 0.9 seconds of thinking time between the teacher asking a question and having to respond. Try increasing wait time by three seconds to allow learners to process the question and begin to order their thinking. Increasing thinking time can improve the quality and depth of responses.

Think-pair-share

Think-pair-share is a strategy often used by teachers to enable learners to explore and respond to questions together. It is important to give learners time to think individually before discussing with a partner then sharing ideas with the whole class.

Example

Think −Think about what you already know about volcanoes. Jot it down.

Pair − Discuss your ideas with your partner.

Share − Share and pool your ideas as a group. Be prepared to give feedback to the rest of the class.

See, think, wonder

See, Think, Wonder is a technique from the Project Zero team at Harvard University that asks students to look at a topic, an image, an artefact, a piece of art or similar and ask three questions:

What do you see?

What do you think?

What do you wonder?

Pose, pause, pounce, bounce

Pose − pose a challenging question. Open questions work most effectively in this context.

Pause − wait and give learners thinking time. In order to give enough time, discipline is needed. Aim to give at least seven seconds.

Pounce − insist on no hands up and pounce on a learner to provide an answer.

Bounce − bounce responses around the class, giving learners the opportunity to develop their response. This could include adding ideas, challenging them, illustrating them or taking them in a new direction. Use minimal encouragement to bounce, for example ‘and..’, ‘but…’, ‘really...’, ‘what else…’

Example

Pose −Think about the word ‘conflict’. What different types of conflict are there?

Pause − wait seven to 10 seconds.

Pounce − Halima, tell me a type of conflict you identified.

Bounce − Can you build on this?... And…And...Really?... What else?...What else?

Big questions

These are sometimes called fertile questions or enquiry-based questions.

They are often:

- engaging − they get learners interested;

- open − there is no definitive answer and often there are a number of possible answers;

- rich − they require learners to grapple with them and think hard;

- connected − they link to universal ideas and themes, giving them relevance; and

- challenging− they can have ethical, political or social and emotional aspects.

Examples of big questions

- What does it mean to belong?

- How did computers change our world?

- What is language?

- How could we eradicate hunger across the world?

- How can we reverse the deforestation of the rainforests?

- What are the big questions for your subject?

Socratic questioning

The Socratic method promotes active learning by taking a six-step approach to asking open questions and then probing for deeper thinking, learning and understanding. You can use the words in bold across all subjects.

- Clarify − what did you mean when you described global tourism as a good thing

- Challenge assumptions − does this mean that you think the development of global tourism is always a good thing?

- Probe for evidence and reasons − what examples can you give to show that global tourism is good?

- Consider different viewpoints and perspectives − do you think that everyone thinks global tourism is positive? Who might not agree with this?

- Consider implications and consequences − what if global tourism declines

- Question the question − do you still think that global tourism is a good thing?

What do you see? What do you think? What do you wonder?

What do you see? What do you think? What do you wonder?

5. Strategies for promoting, deepening and extending thinking

‘I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only teach them to think.’

Wait time

It is estimated that learners on average only have 0.9 seconds of thinking time between the teacher asking a question and having to respond. Try increasing wait time by three seconds to allow learners to process the question and begin to order their thinking. Increasing thinking time can improve the quality and depth of responses.

Think-pair-share

Think-pair-share is a strategy often used by teachers to enable learners to explore and respond to questions together. It is important to give learners time to think individually before discussing with a partner then sharing ideas with the whole class.

Example

Think −Think about what you already know about volcanoes. Jot it down.

Pair − Discuss your ideas with your partner.

Share − Share and pool your ideas as a group. Be prepared to give feedback to the rest of the class.

See, think, wonder

See, Think, Wonder is a technique from the Project Zero team at Harvard University that asks students to look at a topic, an image, an artefact, a piece of art or similar and ask three questions:

What do you see?

What do you think?

What do you wonder?

Pose, pause, pounce, bounce

Pose − pose a challenging question. Open questions work most effectively in this context.

Pause − wait and give learners thinking time. In order to give enough time, discipline is needed. Aim to give at least seven seconds.

Pounce − insist on no hands up and pounce on a learner to provide an answer.

Bounce − bounce responses around the class, giving learners the opportunity to develop their response. This could include adding ideas, challenging them, illustrating them or taking them in a new direction. Use minimal encouragement to bounce, for example ‘and..’, ‘but…’, ‘really...’, ‘what else…’

Example

Pose −Think about the word ‘conflict’. What different types of conflict are there?

Pause − wait seven to 10 seconds.

Pounce − Halima, tell me a type of conflict you identified.

Bounce − Can you build on this?... And…And...Really?... What else?...What else?

Big questions

These are sometimes called fertile questions or enquiry-based questions.

They are often:

- engaging − they get learners interested;

- open − there is no definitive answer and often there are a number of possible answers;

- rich − they require learners to grapple with them and think hard;

- connected − they link to universal ideas and themes, giving them relevance; and

- challenging− they can have ethical, political or social and emotional aspects.

Examples of big questions

- What does it mean to belong?

- How did computers change our world?

- What is language?

- How could we eradicate hunger across the world?

- How can we reverse the deforestation of the rainforests?

- What are the big questions for your subject?

Socratic questioning

The Socratic method promotes active learning by taking a six-step approach to asking open questions and then probing for deeper thinking, learning and understanding. You can use the words in bold across all subjects.

- Clarify − what did you mean when you described global tourism as a good thing

- Challenge assumptions − does this mean that you think the development of global tourism is always a good thing?

- Probe for evidence and reasons − what examples can you give to show that global tourism is good?

- Consider different viewpoints and perspectives − do you think that everyone thinks global tourism is positive? Who might not agree with this?

- Consider implications and consequences − what if global tourism declines

- Question the question − do you still think that global tourism is a good thing?

6. Getting learners to ask better questions

If we drew a pie chart of who asks the most questions in the classroom, it would more than likely show that teachers ask more questions than learners. Encouraging learners to be curious and ask more questions is important.

Building on See, Think, Wonder, colleagues at Harvard Project Zero provide lots of different routines to get learners thinking and asking more questions. An excellent example is Question Starts which requires learners to come up with thought-provoking questions on a topic.

Here is an example for your learners to try:

1. Brainstorm a list of at least 12 questions about electric cars. Use the following beginnings to questions to help you think of interesting questions.

- Why...?

- What are the reasons...?

- What if...?

- What is the purpose of...?

- How would it be different if...?

- Suppose that...?

- What if we knew...?

- What would change if...?

2. Review your brainstorm list and put a star by the questions that seem most interesting. Then, choose one or more of the starred questions to discuss for a few moments.

3. Reflect on any new ideas − do you have any ideas about the topic, concept or object that you didn’t have before?

An effective questioning checklist

In the classroom, teachers have a great opportunity to create the right climate for effective questioning. The helpful checklist below can help you to establish the conditions for success in the classroom.

Use this checklist to get started.

- Agree procedures to create a safe classroom where everyone feels valued. Do this clearly and display the procedures each lesson.

- Know your learners well so that you can plan and target questions carefully using a no hands up approach. This can support reluctant learners and help to manage dominant learners.

- Plan the questions you will use to promote thinking and assess learning. Also, plan who you will ask to make sure that you cover the class effectively.

- Give students thinking time so that they can process the question and come up with their ideas.

- Value all contributions and make the classroom a safe space for learners to test their ideas, take intellectual risks and make mistakes.

- Use positive language such as ‘That was a great mistake, what can we learn from this?’ to encourage learners to see the value in making mistakes.

- Provide opportunities for constructive feedback − teacher to learner, learner to teacher and learner to learner.

- Give all learners a voice − don’t allow particular learners to dominate or opt out. Use non-verbal signals such as eye contact, nodding or hands out to invite responses.

- Add an extra challenge by asking a follow-up question.

- With large groups, try out whole-class response systems such as hinge questions, mini-whiteboards, thumbs up and thumbs down to manage feedback.

- Encourage collaboration and dialogue, using strategies such as think, pair, share. This helps learners to generate questions and more-developed responses. It also supports quiet or reluctant learners with their contributions.

Next Steps

‘Every teacher needs to improve, not because they are not good enough, but because they can be even better.’

Reflective practice is a fundamental part of the Cambridge Teacher Standards because it helps teachers evaluate the impact of their teaching on learning. Having a positive relationship with reflective practice helps teachers develop and thrive. However, it is useful to remember that reflection is not something that you have to do alone. Often it can be productive to reflect with a mentor, a trusted colleague or even with learners.

Watch this video and think about what might be the best next step for you

A great starting point is to examine or think about your questioning.

Use the prompts below to support the reflection process:

- When is your questioning most effective? How do you know?

- When is your questioning least effective? Why is that?

- What would learners say about your questioning?

- Which questioning strategies do you use regularly? What is their impact?

- When did you last do something differently or try something new?

- What would great questioning look like in your classroom?

- What could you do to make your questioning better?

The ‘Ten Questions’ approach to developing your questioning

For teachers who would like to improve their questioning, a good strategy to use is ‘Ten Questions.’

Follow the six steps below.

- Ask a trusted colleague to visit a lesson of your choice at an agreed time.

- On a sheet of paper, ask them to write down the first 10 questions as you ask them.

- When they have written down the 10 questions you have asked, they give the piece of paper to you and leave the lesson.

- After the lesson, sit down and reflect on the questions you have asked. You can do this on your own or with a trusted colleague. Key questions are: What do you notice about your questioning? Was there anything interesting or that surprised you? What are you going to do to make your questioning better? How will you know if this has made a difference to learning?

- Make one or two changes to your questioning and practise them.

- Repeat this process two or three times and evaluate your progress and impact.

Want to know more?

Here is a printable list of interesting articles and websites.

Glossary

Analyse ─ To study or examine something carefully and in detail in order to understand it more.

Assessment for learning ─ Essential teaching strategies during learning that help teachers and students evaluate progress in terms of understanding and gaining skills and providing guidance and feedback for future teaching and learning.

Classroom climate ─ How the classroom feels, for example it feels like a safe place to take risks and make mistakes. Ambrose and colleagues (2010) define classroom climate as “the intellectual, social, emotional, and physical environments in which our students learn” (Ambrose, S.A. et.al. (2010). How Learning Works Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass p.170).

Closed questions ─ A question that can be answered with either a single word (usually ‘yes’ or ‘no’) or a short phrase, and for which the choice of answers is limited.

Critical thinking ─The ability to analytically assess and evaluate particular assertions or concepts in the light of either evidence or wider contexts.

Direct questioning ─ A questioning technique in which the teacher chooses a learner to answer a question, instead of learners putting up their hands to answer a question.

Evaluate ─To judge or determine the quality, importance, amount or value of something.

Hinge questions ─ A hinge is a point in a lesson when you need to check if students are ready to move on and, if yes, in which direction. A hinge-point question is a diagnostic question that you ask your students when you reach the hinge. The responses tell you what you and your learners need to do next.

Low-stakes quizzes ─ Low-stakes quizzes are short quizzes that have no impact or influence on grades or results. They are often used to find out what students do and don’t know. They can be used to identify misconceptions or learning that is not yet secure.

Open questions ─ A question that cannot be answered with a one-word answer, for example, ‘What do you think about global warming?’

Reflective practice ─ How the teacher continuously learns from the experience of planning, practice, assessment and evaluation and which can help them improve the quality of their teaching and learning over time.

Retrieval practice ─ A strategy that requires learners to deliberately recall what they know and remember.

Scaffolding ─ The teacher provides appropriate guidance and support to enable learners to continue to build on their current level of understanding to gain confidence and independence in using new knowledge or skills.

Wait time ─ The amount of time a teacher waits after asking a question and before choosing a learner to answer it.

Zero-stakes testing ─ A zero-stakes testing approach is when learners test or assess themselves. Their answers or results have no impact on grades or results.