Getting started with

Key Concepts

What are key concepts?

A concept is a mental representation of a class of things. Concepts are a way of grouping or categorising things to make sense of a complex and diverse world. For example, we have a concept of 'chair' into which fits a huge variety of actual chairs – tall ones, small ones, wooden ones, metal ones, old ones, new ones, fancy ones, plain ones and so on.

Through this grouping we create a shared framework for understanding, communication and action. Because we have the shared concept of 'chair', one person can ask another to get a chair from the next room without the second person returning with a table! Similarly, we have shared concepts of 'lamp', 'plant', 'house', 'road' and so on.

‘…everyday concepts are ‘picked up’ unconsciously by everyone in our daily lives and are acquired through experience...’ Young, (2015)

Each school subject involves a large number of concepts. These range from concepts that refer to simple, concrete things (for example, 'bunsen burner', 'watercolour paint', 'basketball') to those that refer to complex, abstract things (for example, 'power', 'love', 'religion').

‘Key’ concepts are ones judged to be particularly important in a certain context. A similar term is ‘big’ concepts. This includes a sense of scale and range, as well as importance, within the subject.

The concepts a person or group chooses as ‘key’ in a subject will vary according to their view of that subject and their purpose in selecting the set of key concepts. A teacher working with young children in science may choose a different set to an academic chemist working with undergraduates. Often, the concepts chosen as ‘key’ are complex and abstract, such as 'place', 'chronology' or 'grammar'. However, they could also be simpler and concrete, such as 'crown', 'tree' or 'coin'.

In this video, Dr Liz Taylor introduces key concepts and why they might or might not be shared with learners.

In the rest of this guide, we will discuss the benefits of using key concepts. We will look especially at their benefits in helping us to carry out high-quality planning for progression. We will look at the research behind key concepts and consider some practical ways of using them in medium and long-term planning.

Throughout, you will be encouraged to reflect on how you can use key concepts when planning your curriculum. At the end, there is a glossary of key words and phrases and some suggestions about what you could do next.

What is the research behind using key concepts in curriculum planning?

Concept formation is an area of research in psychology. It refers to how people acquire or learn to use concepts. In the ‘Big Book of Concepts’, Gregory Murphy summarises research in this area of psychology. Concept formation traces the way people develop an understanding of their experience, what systems of categorisation they develop, and how they learn and use these systems. This research often focuses on concepts of fairly basic, concrete things, for example, types of animals and their features.

Also, there is a range of education research about what children know and how they learn about particular concepts that form part of school subjects. Examples of these concepts include 'sustainability' in geography (Walshe, 2008) and 'chemical elements' in science (Taber, 1995). In history, Lee & Shemilt (2004, 2009) carried out research into the progress learners make in their understanding of key concepts. In science and related subjects, research into key concepts often focuses on identifying and dealing with learners’ misconceptions or ‘alternative conceptions’. (These are misunderstandings or previous ideas that can act as barriers to further learning on that topic.)

This research is useful when planning and teaching about particular concepts. It helps us to understand misconceptions young people may have about concepts and how we can support learners to make progress.

There are various approaches to thinking about types of concepts. Using substantive, second-order and threshold concepts (see below) is particularly helpful to inform high-quality planning for progression.

- Substantive and second-order concepts

The division between substantive and second-order concepts stems from ‘Science, Curriculum, and Liberal Education’, a selection of essays on the structure of disciplines by Joseph Schwab (1978).

In this approach, there are two sets of concepts.

• Substantive concepts: these are part of the ‘substance’ or content knowledge in a subject. (For example, in geography, these might include 'river', 'trade', 'city' or 'ecosystem'.)

• Second-order concepts: these shape the key questions asked in a subject and organise the subject knowledge. (For example, a set of second-order concepts for history might include 'cause and consequence' (causation), 'change and continuity', 'similarity and difference', and 'historical significance'.

There will often be an overlap of substantive concepts between subjects. A student might learn about 'renewable energy' in science, geography, economics and politics. There may even be some overlap of second-order concepts, for example ‘change’ in both history and geography. It is the particular combination of substantive and second-order concepts that makes each discipline distinct and unique.

‘Content, therefore, is important, not as facts to be memorised…but because without it students cannot acquire concepts and, therefore, will not develop their understanding and progress in their learning.’ Young (2015)

2. Threshold concepts

A threshold concept is one that, once understood, modifies learners’ understanding of a particular field and helps them to make progress. It helps them to go through a ‘doorway’ into a new way of understanding a topic or subject. The idea comes from a research project on teaching and learning in undergraduate courses (Meyer and Land, 2003). While ‘core’ concepts build on existing learning, layer by layer, threshold concepts open up a new way of thinking.

‘…there may thus be a transformed internal view of subject matter, subject landscape, or even world view.’ Meyer & Land (2003)

A threshold concept is likely to be difficult for a learner to grasp, but once they understand it their learning can move to a new level within the discipline. It can be hard for a learner to make progress if they don’t understand key threshold concepts.

There is debate over which concepts might be identified as ‘threshold’ in a particular discipline. The original work in this area was in economics, but researchers in engineering, computing, geography and healthcare have also become interested in this idea. For example, suggested threshold concepts include 'sustainability' for geography, 'complex number' for mathematics and 'opportunity cost' for economics.

As you watch the video of Dr Liz Taylor reflecting upon her own learning, look back over your own learning. What was a threshold concept for you?

What are the benefits of using and thinking about key concepts in teaching and learning?

Key concepts help develop a teacher’s understanding.

Thinking carefully about key concepts can help you and your subject department better understand the nature of the discipline you teach and help your learners make progress.

Key concepts help develop learners’ understanding.

Talking about key concepts and their role in planning within a department helps you focus on what is important within your subject and how you will help learners make progress in understanding these things.

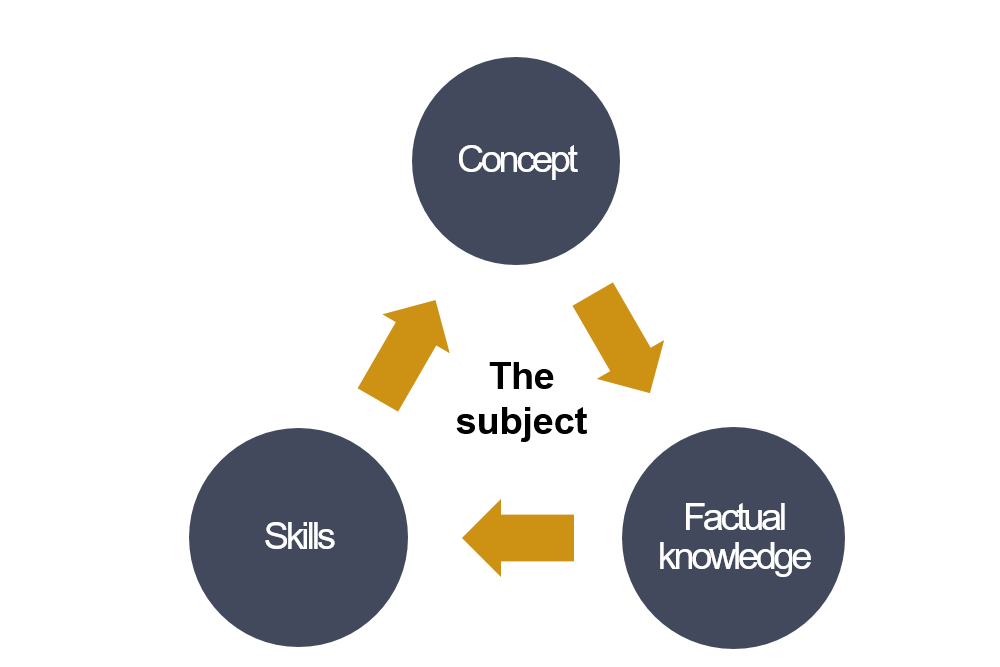

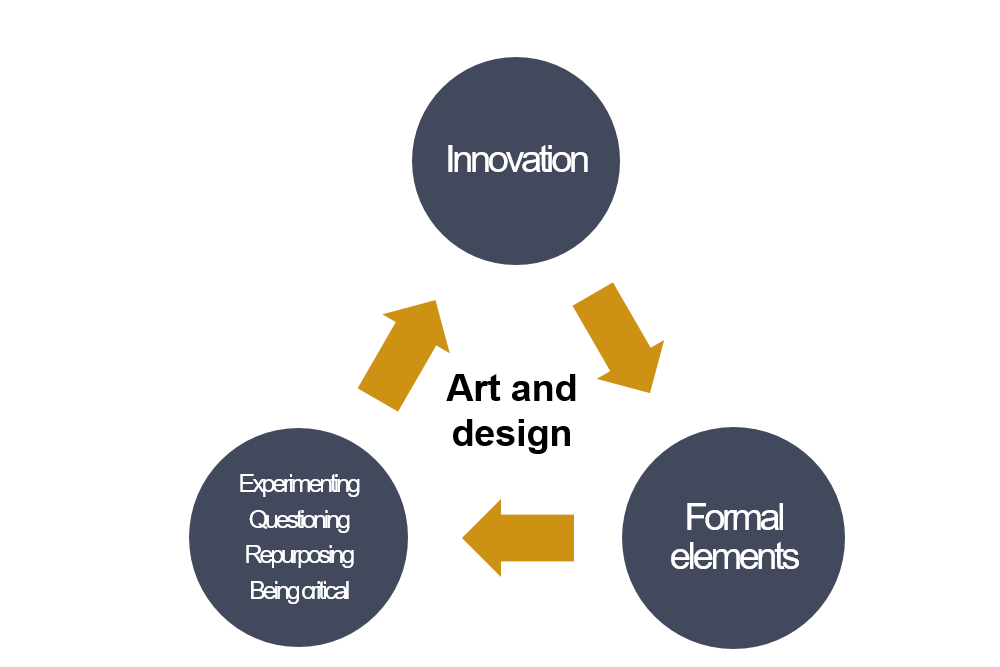

Key concepts help develop understanding.

Teaching and planning with key concepts in mind prevents learning being about gathering information. It helps to develop understanding by offering opportunities to link, review and put knowledge into context (see diagram below). In this way, awareness of key concepts can help deepen learners’ knowledge and understanding. Of course, learners should also be able to apply the skills that are needed to work successfully within a discipline.

Key concepts help to develop powerful knowledge.

Powerful knowledge is knowledge that is embedded within a subject and made available to all learners. In the book ‘Knowledge and the Future School’, educationalist Michael Young argues that ‘In acquiring subject knowledge they are joining those ‘communities of specialists’ each with their different histories, traditions and ways of working.’ (Young, 2015.) Access to this powerful knowledge means a student in a physics class should be aiming to think and behave like a physicist, a student in a geography class should be aiming to think and behave like a geographer and so on. Key concepts help with this because conceptual knowledge, factual knowledge and skills together create a distinct subject discipline through which learners can progress.

Key concepts help to connect learning.

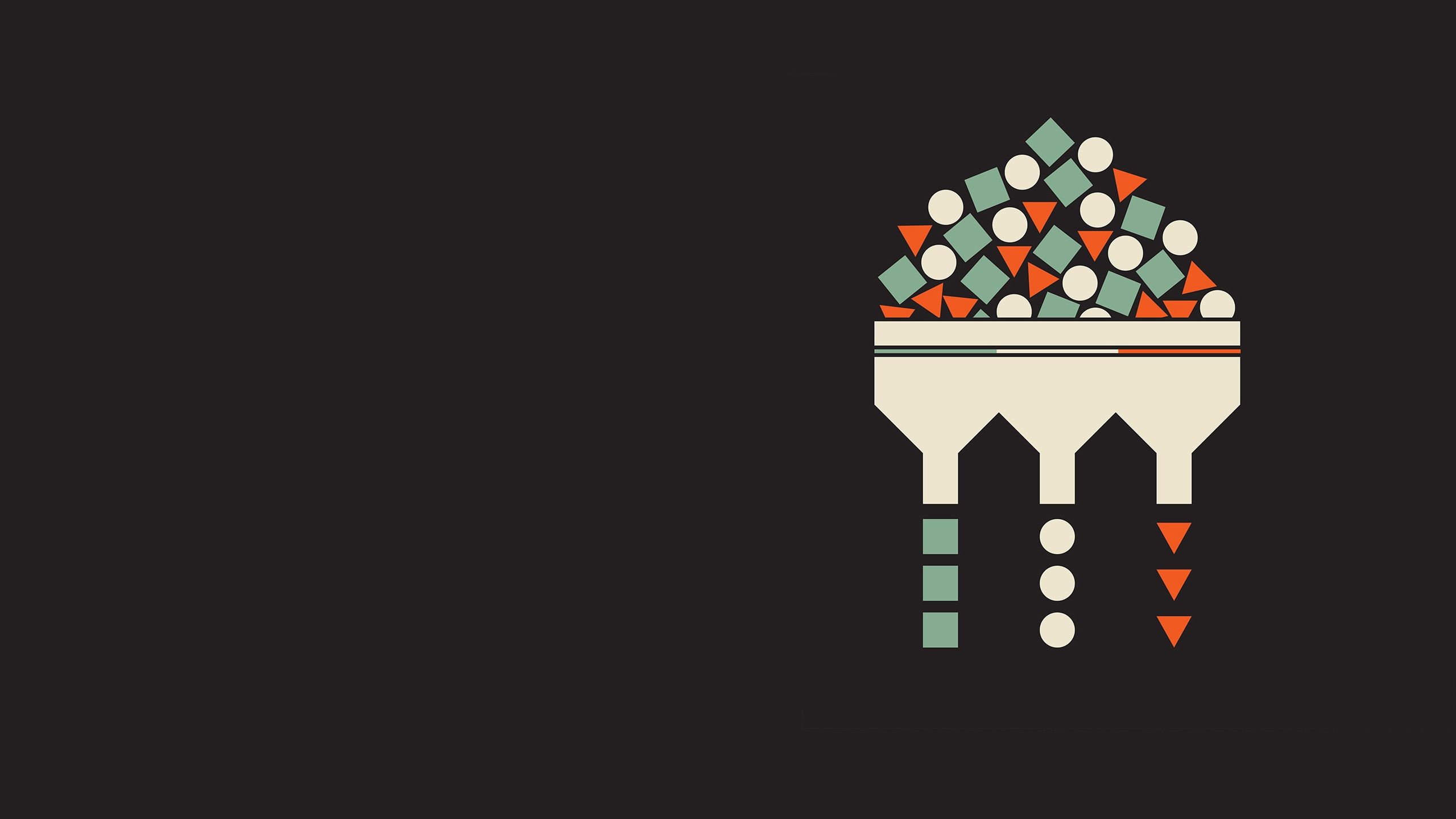

A key concept will often link one topic to another. In economics, the key concept of 'opportunity cost' links other areas of the curriculum such as production possibility frontier and the theory of comparative advantage. The diagram below (adapted from ‘Approaches to learning and teaching Science’) shows the relationship between some factual knowledge and a key concept in biology. At first, the factual knowledge could seem unrelated to a learner. By keeping the key concept in mind when planning and teaching, it is possible for the learner to make links and put their understanding into context. As their teacher, you have to help learners see these links, as this will not necessarily happen without guidance.

In the video, Dr Liz Taylor suggests that deciding the key concepts in your subject is a challenge for teachers. Do you agree? How would you overcome this challenge?

Common misconceptions

There are a number of misconceptions around the use of key concepts and their role within a subject.

1. Concepts only refer to ‘big ideas’.

We have mental representations of big, abstract ideas (such as 'power' or 'change'), but we also have concepts of small, concrete things like 'pen', 'biscuit' or 'chair'. When planning your curriculum think carefully about how you will build learning which takes students from knowledge of the smaller concepts to understanding the more abstract ideas in a discipline.

2. There must be one right set of key concepts for each school subject.

If there is, we haven’t found them yet! Different people and groups have different views on this. Subjects are constantly growing and changing, so it is unlikely there could ever be just one agreed set of key concepts for all learning situations. However, it is often useful in a particular context (for example, an examination specification) to present a set of key concepts, as these can then be used to help plan the curriculum.

3. If a concept isn’t in the agreed ‘key’ set for a subject, it isn’t important.

Each subject includes many substantive (subject content) concepts that are very important as building blocks for learners’ understanding, even if they aren’t in the ‘key’ list. If these concepts are not thoroughly understood, learners may not be able to grasp the bigger, overall ideas that shape the discipline.

4. Key concepts alone make up subject-specific vocabulary.

Each discipline uses specific language that has a distinct meaning to that subject. Key concepts may make up some of this language, but it is important to encourage learners to develop their use of subject-specific vocabulary beyond the key concepts alone. This will mean learners are able to fully explain their understanding of the key concepts.

Imagine a colleague has one of the misconceptions mentioned in the video. How could you support your colleague to develop their understanding of key concepts?

Key concepts in practice

Using key concepts can be one way of helping you plan for progression. There are some suggestions for doing this below. (Of course, there are also lots of other frameworks you could use.)

A helpful exercise in planning for progression is to set out the knowledge, key concepts and skills that you want learners to develop. This is useful as it makes sure there is a suitable balance between these three elements over the medium and long term. ‘Suitable’ doesn’t necessarily mean equal or separate in terms of curricular time. In practice, the three elements are linked in learning (see the diagrams below) but each should be evident in the scheme of work to the relevant degree of emphasis. Another approach to planning may be taken in subjects such as maths. In ‘Approaches to learning and teaching Mathematics’ there are five areas of learning needed for mathematical proficiency. Conceptual understanding is one of these five. This planning framework also requires balance when planning and teaching these five areas.

Key concepts in medium-term planning

Medium-term planning is preparing for learners’ progress and development over a sequence of work. This might be a unit of five to six lessons or longer, depending on the subject and the teaching time available.

One approach to medium-term planning is to design an enquiry sequence that is underpinned by one second-order key concept. This was pioneered in history by the work of educators such as Michael Riley (2000). In this work, Riley refers to second-order concepts as ‘areas of second-order understanding’. He proposed the following features of an enquiry sequence.

• A carefully constructed enquiry question to guide a short sequence of lessons. This question should be rigorous, challenging and intriguing. The wording of enquiry questions is crucial and may take time for you and your department to develop. Enquiry questions do not have to lead into individual or group research projects. They are a way of getting learners to focus their thinking, and can be used in a whole range of activities and plans.

• The question should ‘place an aspect of historical thinking, concept or process at the forefront of pupils’ minds’ (Riley 2000). This is where the second-order concept comes in. Again, it takes careful thought to phrase the question in the correct way to make sure that the concept is the real driving force.

• Lesson by lesson, learners gain the substantive content knowledge needed to answer the enquiry question effectively.

• It should result in an outcome activity (an essay, wall display, radio script and so on) in which the enquiry question is genuinely answered.

Teachers skilled in creating enquiry sequences deliberately construct puzzles for their classes, introducing new elements to the ‘story’ that cause pupils to question their initial ideas and help them develop more detailed responses as the sequence progresses. This will help learners to think critically and develop a deeper understanding of a topic or theme. This is very different to the superficial approach to enquiry questions in which they form little more than the lesson title.

Example of an enquiry sequence

Context: The geography department at Loftyhill School teach a 12-hour unit of work on the USA with 13- to 14-year-olds. Their current scheme of work is quite traditional. It covers the main elements of physical and human characteristics of the USA, including types of employment and links with other countries. It is strong on factual knowledge and also builds understanding of substantive concepts such as 'climate', 'urban areas', 'trade' and 'employment'.

Reflection: The department are worried that their planning does not deal with broad geographical ideas. They would also like to find a way for their planning and delivery to involve and interest pupils more. The department are experimenting with using key concepts such as 'interaction', 'diversity' and 'change' to inform their medium-term planning (Taylor 2008). In the article ‘Key concepts in medium term planning’ (2008), Liz Taylor discusses an approach to medium-term planning in geography, based on key concepts.

Action: They decide to divide the 12-hour unit into two six-hour enquiry sequences. The first will be based around the key concept of 'diversity'. To get learners interested, they decide to ask: ‘Where should the Smith family move to in the USA?’. They set up a lively activity in which learners play the part of relocation agents hired to look at four locations in the USA. The locations are chosen by the teacher to give a taste of physical, environmental and human diversity. After a general introduction to the USA, learners work in small groups to research and evaluate one location per lesson, applying these to the needs of the family and making a short oral presentation to answer the question in the final lesson.

Outcome activity: An individual written homework that allows learners to reflect on the extent of human and physical diversity within the USA.

Next steps: This unit would then provide an excellent foundation for a further enquiry sequence which considers the nature and extent of the key concept of 'interaction' between the USA and other countries in the world, particularly relating to migration and trade links.

Having read the example above, what key concept could you base an enquiry sequence on? How will you know your learners are building an understanding of that key concept?

Key concepts in long-term planning

When using key concepts to shape your long-term planning you will need to think carefully about how to use them to develop learners’ understanding and make sure your learners make progress. Consider the following points.

Planning for progress over the long term.

Think about the learning journey of the pupil. How will they gain an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the key concepts that shape knowledge into a discipline?

Provide opportunities to revisit key concepts.

This will help learners to develop increasingly sophisticated levels of understanding over time. Substantive concepts can be organised into hierarchies, in which a learner needs to grasp a more basic concept before going on to the more complex one.

Think about threshold concepts.

Where should you position these for learners to be most likely to pass through the ‘doorways’ to new ways of looking at a topic or subject? Is just one encounter with a threshold concept enough, or will your learners need to revisit this tricky concept a number of times to be able to understand it?

It will be useful to draw on research on key concepts in your subject, if this is available. However, this is also an area where every teacher can develop their understanding and practice by carefully observing and reflecting on their own students’ learning.

In this video, Dr Liz Taylor discusses why it is helpful to use key concepts in planning and whether this is different at different levels of learning.

Create a list of all the concepts in your subject. Which ones would you say are ‘key’? Ask a colleague to create their own list and compare it with your own. Where are the similarities and differences?

A key concepts checklist

If you are new to using key concepts to support curriculum planning, it will help to consider the following points and even to discuss them with your subject department.

Think carefully about the key concepts in your subject.

Start by listing all the concepts that come to mind, then highlight the ones you would consider to be ‘key’. Cross-check against any lists available in examination specifications, textbooks or curriculums. Do the lists differ in any way? Remember that it is fine for different people to have different views of what makes a key concept. However, your examination syllabus will have been written with a recommended list in mind, so you should make sure that you include these key concepts in your own lists.

Review the place of key concepts in your current curriculum documents.

Is appropriate emphasis on each of your key concepts clear across your current planning documents? If not, choose one medium-term plan you want to revise, such as a scheme of work for a topic you will be teaching. You might like to start by thinking of one key concept which you think is particularly relevant (perhaps a threshold concept). Although the topic probably involves a number of substantive concepts, and may help learners understand more than one key concept, it helps to give particular emphasis to one key idea.

Devise a medium-term plan.

Plan an enquiry sequence or other approach to learning in which students will have the opportunity to get to grips with a particular key concept (see the example above). Try creating an enquiry question that will involve and interest your learners and which can be answered in a substantial outcome activity (see above). How will the sequence help learners make progress in their understanding of the key concept?

Try it out!

Teach using your medium-term plan. Be mindful of the key concept you are exploring with your learners and remember to remind them to think about this concept when appropriate.

Reflect on the lesson sequence

Evaluate how far the lesson sequence allowed learners to develop their understanding of the key concept. Use learners’ written work or other material (responses to class discussion, for example) as evidence. What did they learn? How do you know? Did you get the balance between building knowledge, building skills and understanding concepts that you were aiming for? If not, what would you change next time? How will you move learners on from this point?

Next Steps

Reflect back over your own learning of your subject.

Can you suggest one or more ‘threshold concepts’ in your discipline? What changed your perspective and modified your view of an issue or field?

Read about your discipline.

To what extent is there agreement on ‘key’ concepts within the academic and teaching communities for your discipline? Can you see how there might be a difference between substantive and second-order concepts for your discipline? Is there any discussion of this in the professional literature you have access to?

Reflect on your teaching.

In what ways do you prompt and respond to learners’ previous ideas on topics that you teach? Are there any common misconceptions in your subject? How will you challenge these misconceptions to move learning forward?

Think about how you will embed key concepts in your teaching.

Do you think that the key concepts in your discipline should be made clear to learners? If so, how and when would this be most helpful? If not, why not?

Want to know more? Here is a printable list of interesting books and articles on the topics we have looked at.

Glossary

Abstract concept

A concept not associated with any physical object.

Concept

A mental representation of a class of things. A concept may refer to concrete or abstract things for example, 'cat' or 'love'.

Concrete concept

A concept of a physical object or being such as 'spoon', 'dog' or 'football'.

Enquiry sequence

A short series of lessons focused around a carefully developed exploratory question.

Key concept

A concept which people propose or agree to be particularly important within a certain context.

Long-term planning

Preparation for learners’ progress and development over a year or more.

Misconception

An incorrect view or opinion.

Scheme of work

A set of planned units of learning relating to a topic, subject or stage.

Second-order concept

A concept which can be used across all aspects of a subject to organise the substantive knowledge. Second-order concepts form the heart of the characteristic questions asked by a discipline.

Substantive concept

A concept forming part of the substance (content) within a subject.

Threshold concept

A concept which, when fully grasped, will modify learners’ understandings of a particular field.